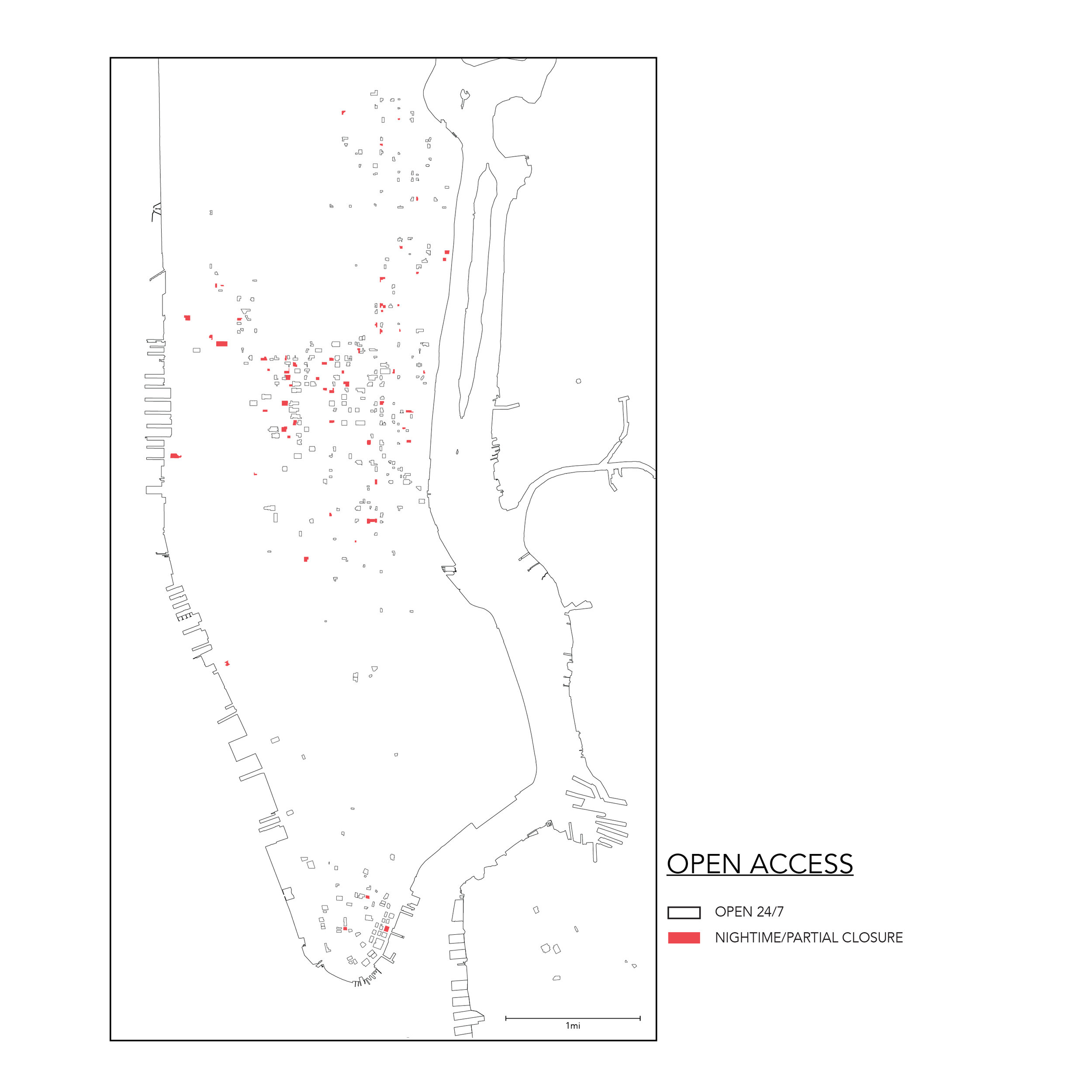

POPS INVENTORY

2018 - ongoing

Independent Research about Privately Owned Public Spaces in NYC

Presented as part of the Inventaires Urbains exhibition and conference at the Ecole de Design at the Universite du Quebec a Montreal

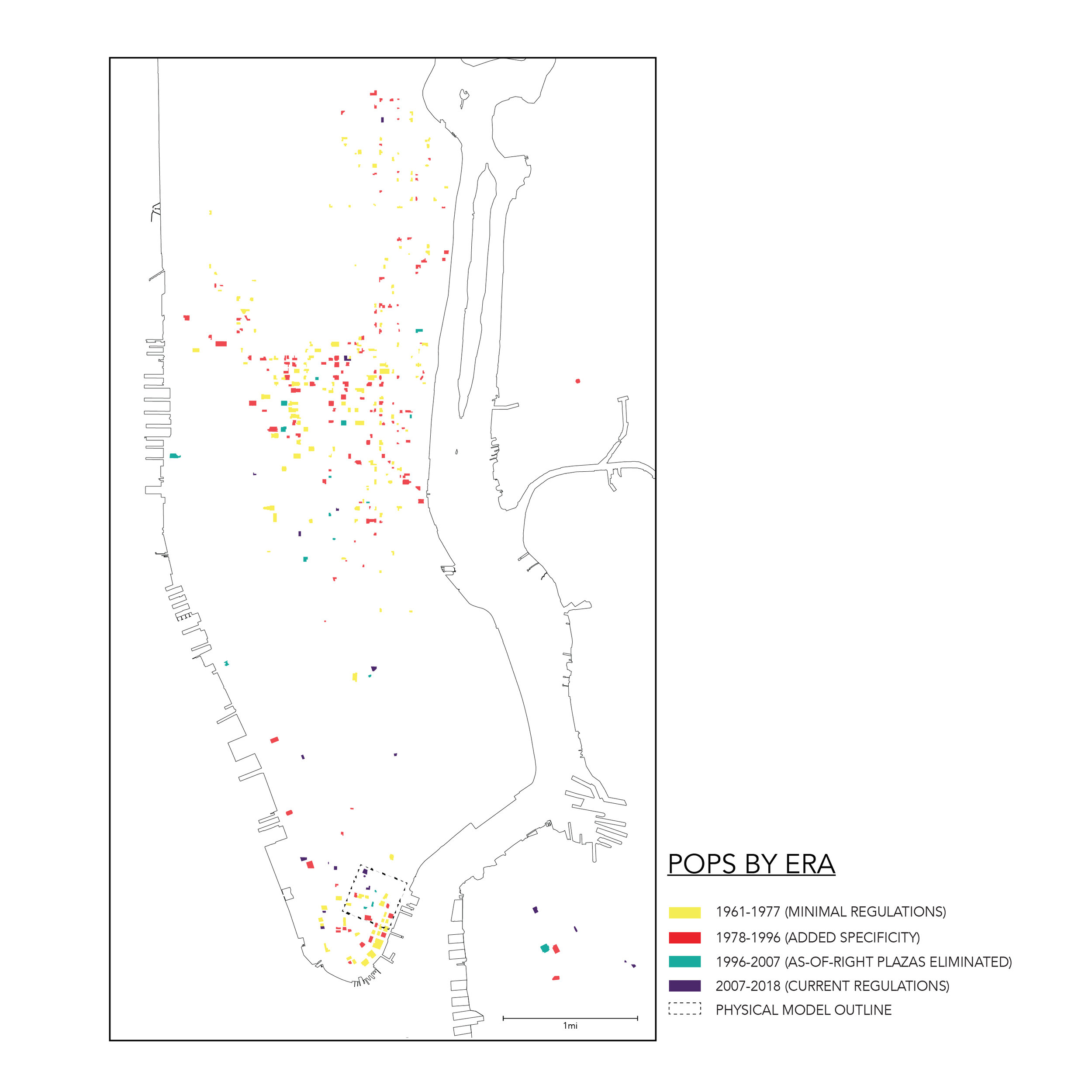

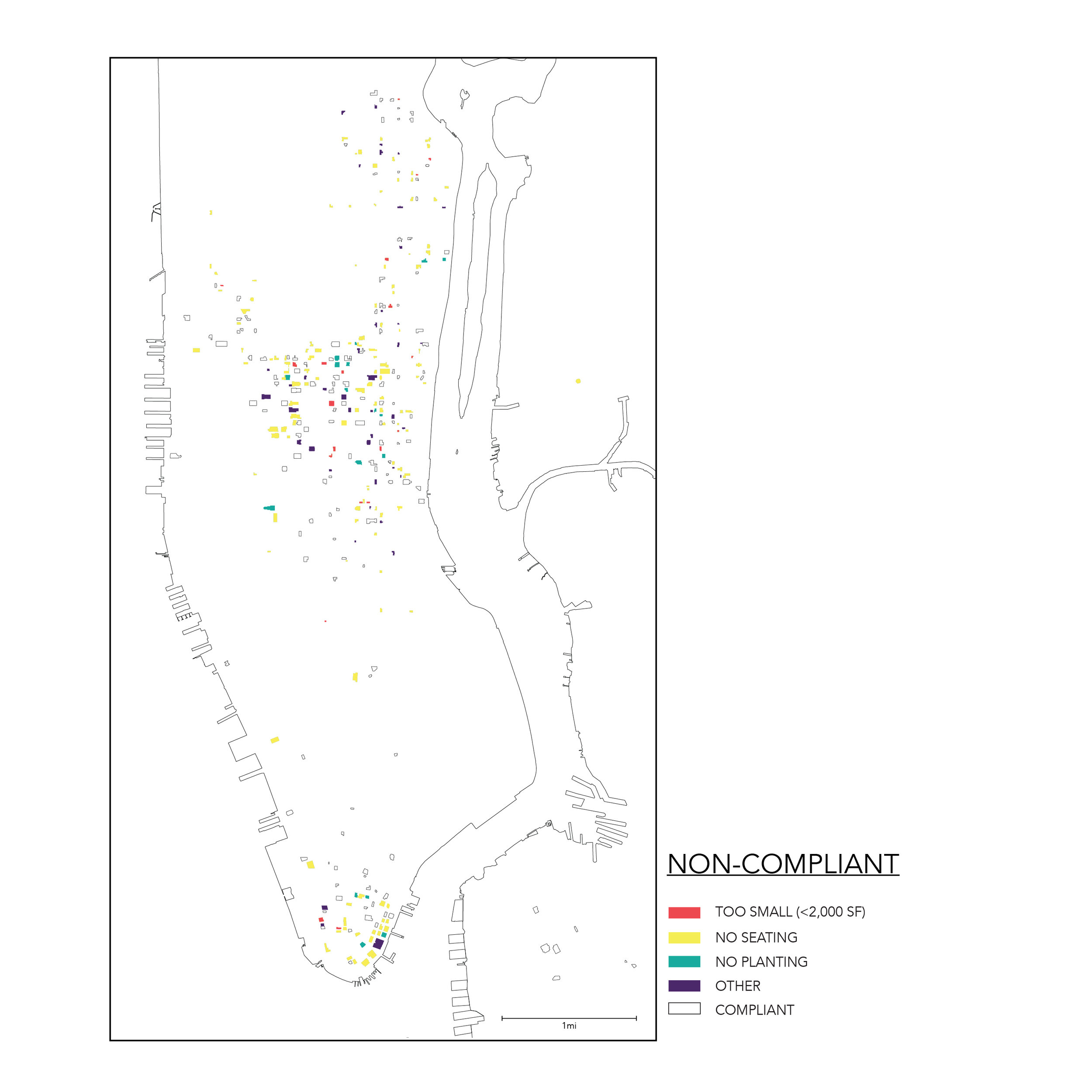

Privately owned public spaces (POPS) offer incentives to developers in exchange for providing an open and publicly accessible space on the premises. These “public” spaces are controlled, maintained, and operated by the property owner and, while regulated by municipal zoning laws, are subjected to the material provisions and behavior guidelines of that private entity. Far from the liberated spaces of the public “right of way” or the freedom of expression associated with iconic public squares such as London’s Hyde Park, POPS restrict public behavior on their grounds to a list of do’s and don’ts.

Nearly two decades after Jerold Kayden’s comprehensive survey of New York City’s Privately Owned Public Spaces, entitled Privately Owned Public Space: The New York City Experience, was published, POPS have continued to transform the city’s composition, as well as that of other cities around the globe. Kayden’s 2000 study found that 41% of the POPS were of “marginal” quality, meaning they provided little urban benefit. Rather than offering dynamic public spaces that augment the publicness of the urban environment, many POPS contribute to a surplus of banal open spaces in cities. Their physical conditions blend together as variations on the same conventional themes: hard surfaces, fixed seating, and limited adaptability. In this way, the public imagination is further constrained within an atmosphere of bland urban sameness. Without distinct identity, these plazas assimilate as a distributed series of non-places, a concept developed by French anthropologist Marc Auge that describes spaces of transience and anonymity.

Such is the condition of urban public space today: a ubiquitous terrain of new urbanism-prescribed benches, water features (not for touching!), and fenced-off grass plots that intend to placate and control occupation rather than to invite it. This kind of “public” space performs more as a neutralizing blanket—muting the possibility of an active, inclusive, and productively agonistic urban environment—than a shared ground for diverse use and expression. According to David Harvey, “The right to the city is far more than the individual liberty to access urban resources: it is the right to change ourselves by changing the city.”[i] The right to change the city today is increasingly provided only to developer-influenced regulation. Instead, alternative and independent visions for public space as we know it are necessary.

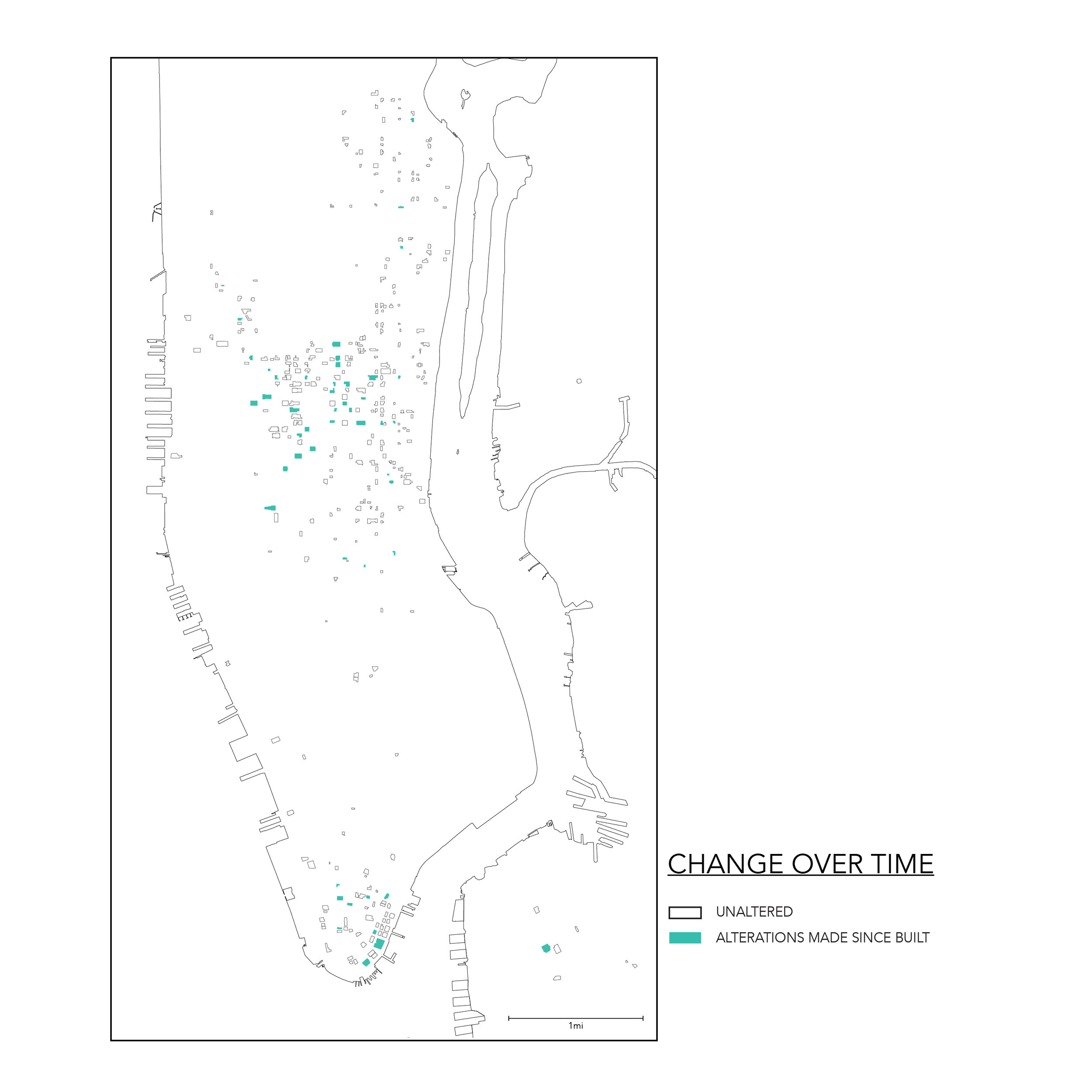

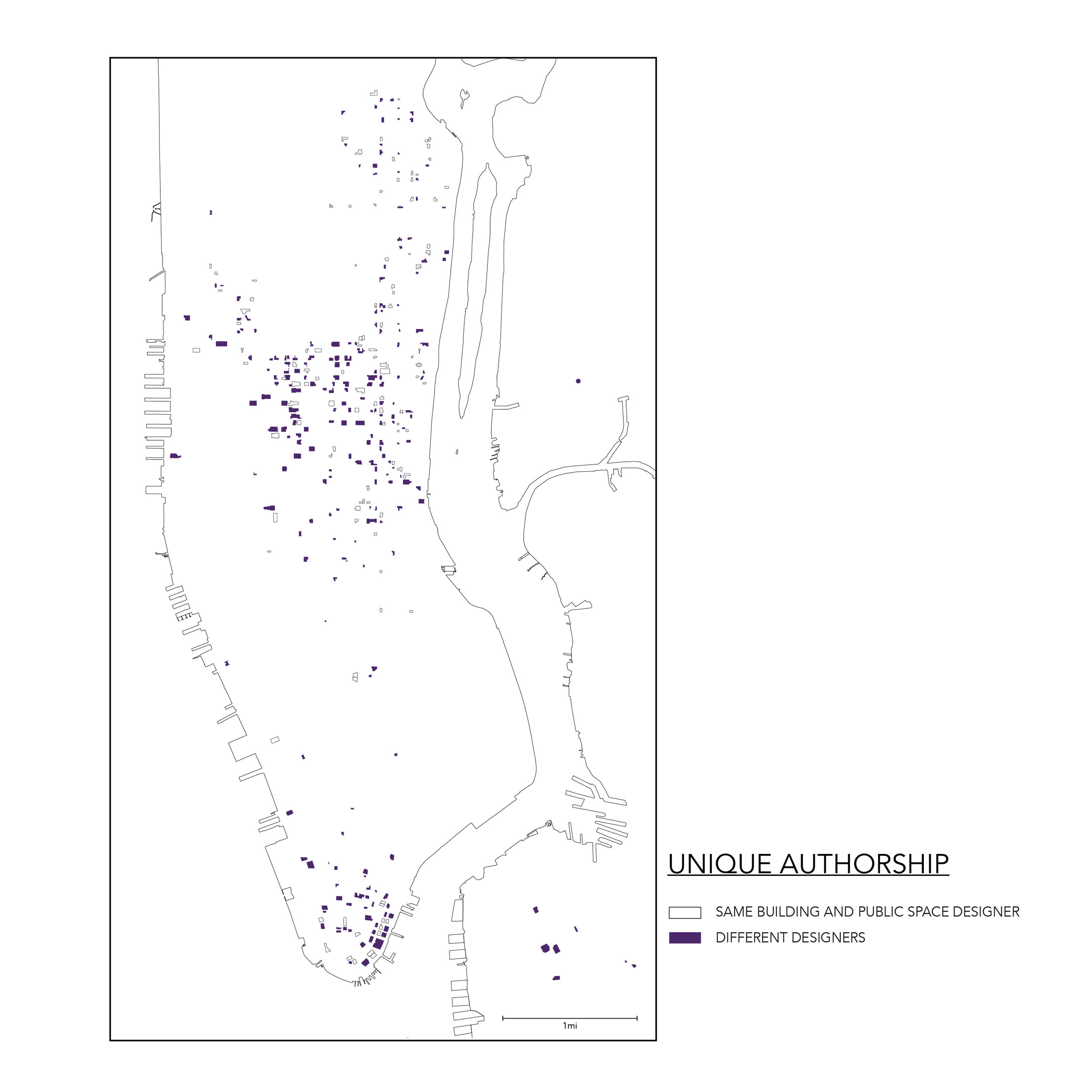

In 2018, the New York City Planning office published extensive open data about POPS, including information such as type, amenities, opening hours, etc. in an interactive map on their website. Combining data analysis and empirical study, “Public Inventory” presents a critical survey of this increasingly prevalent condition of the public realm, identifying problems and proposing possible alternatives. Through the survey and analysis of a sample of the more than 550 POPS in New York City today,[ii] the work creates a foundation for critique through the production of alternative visions and strategies.

[i] David Harvey, “The Right to the City”, The New Left Review, Issue 53, Sep-Oct 2008, https://newleftreview.org/II/53/david-harvey-the-right-to-the-city. Accessed June 1, 2018.

[ii] https://www1.nyc.gov/site/planning/plans/pops/pops.page